“An exemplary coach and better than many school coaches that I’ve come across.”

That was my reply to colleagues who asked about the lesson observation I did for Coach Tim Kwo Liang while he was coaching at Kranji Secondary School last week. My colleagues and I are developing a competency assessment, and Coach Tim had kindly agreed to allow us to use him as a “test subject”.

Coach Tim has been a table tennis coach for more than 20 years. Although he has the relevant technical certifications for the sport, he has not gone through the formal education pathway (classroom lessons followed by a written test) to earn his theory accreditation. Despite that, I found his lesson to be highly organized and engaging (although this was not reflected by his lesson plan). He has a positive approach and made time to personally coach and play against every single one of the 21 students present. He provided quick demos and specific feedback, and nippily modify the drills according to the ability of his students.

The experience with Coach Tim reignited an internal debate that I’ve been having regarding Formal vs Non-Formal coach education. Personally, I’m biased against formal coach education even though both forms of education has helped me develop both as a sport and psychology coach. I feel that coaches learn best when they are coaching, through their own research, and mentorship (even discussions in forums). Hence, over the next few days, I went through some studies (see references at the foot) that have been published on this topic to test against my own bias.

Here are some common findings from these Formal vs. Non-formal studies:

- Formal education may lack context, meaning, and individualization is limited. Since assessment drives learning, coaches may end up learning how to pass the assessment rather than how to coach.

- Less formal opportunities such as workshops, mentoring, peer discussions and even reading are found to be more meaningful and contextualized. Some findings have shown that coaches also learned without the direct guidance of others during their day-to-day coaching activities.

- In a Canadian study, it was found that unguided and self-directed learning provided the largest contribution to youth ice hockey coach development.

- Less formal education may lack quality control, direction, feedback, and innovation.

- Coaches may have difficulties accessing non-formal opportunities due to the competitive nature of sport at all levels, i.e., some coaches who are deemed as competitors or outliers may be excluded from participating in certain workshops or sharing.

- Formal education (e.g., tertiary education) has a better capacity to lead to the development of critical thinking skills, i.e. reflection. Critical self-reflection is vital to continued success for coaches. (i.e., I’m sure we all know of “experienced coaches” who continue to stick to the same old coaching practices despite having coached for decades).

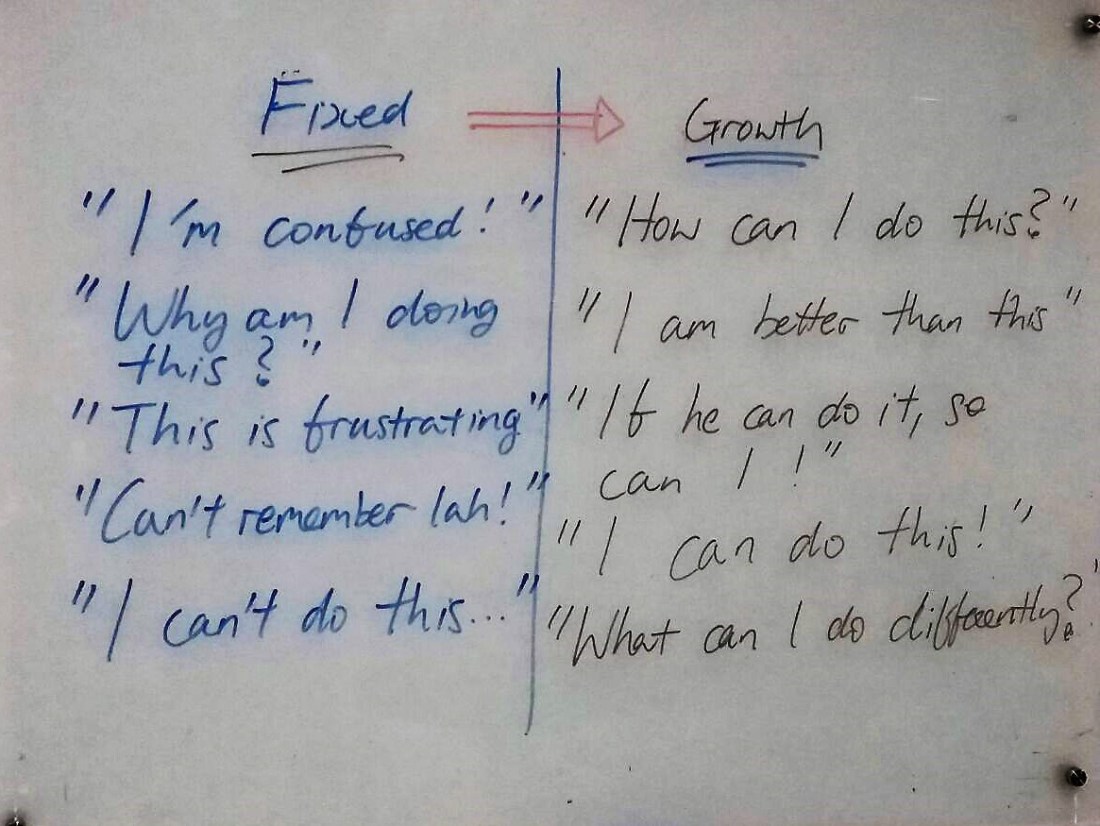

Objectively speaking, both formal and non-formal forms of education should be valued, and there shouldn’t be a dichotomy between the two. However, since the pervasive perception here is that formal education’s better and highly educated (i.e., having a degree in sport science or PE) persons probably make the best coaches, more should be done to recognize and respect the value of non-formal coaching. Any potential disadvantages of non-formal coaching can be rectified by adding elements of structure, reflection, and evaluation. We also need to shift from the traditional classroom “download” style of formal coach education, to one that is more facilitated and applied.

p.s. I reckon this fixation on formal education is not exclusive to sport coaching. Singaporeans and employers (especially the civil service) on a whole still buy into the notion that you need to have a degree in order to be qualified to do a job!

Coach Hansen

References:

Werthner, P. and Trudel, P., A New Theoretical Perspective for Understanding How Coaches Learn to Coach, The Sport Psychologist, 2006, 20, 196-210.

Wright, T., Trudel, P. and Culver, D., Learning How to Coach: The Different Learning Situations Reported by Youth Ice Hockey Coaches, Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 2007, 12, 127-144.

Rynne et al., High Performance Sport Coaching: Institutes of Sport as Sites for Learning